Archetypes: undercurrents for experimentation and ways of seeing

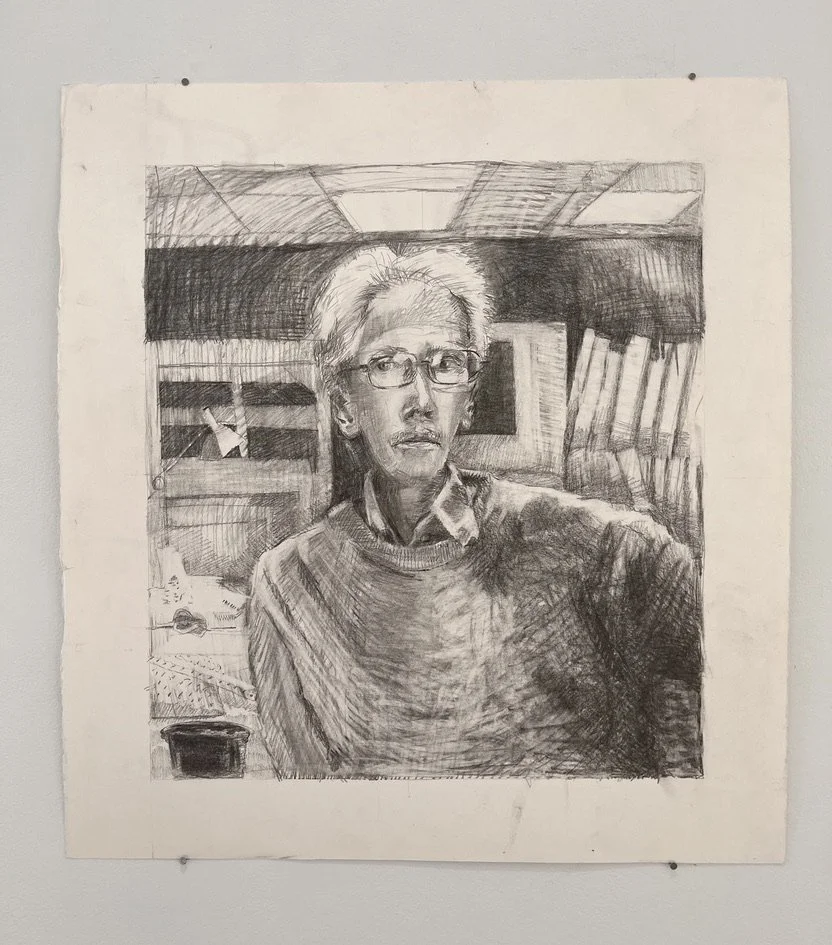

George Glenn’s practice conveys his observations on the concrete, intertwined with his reflections on the structures of his life. His paintings balance memories from his past and references to his present, with an undercurrent of the objects and spaces around him. Throughout his works, still life subjects such as glasses, cups, vases become recognizable motifs. This gallery displays George’s re-envisioning of objects that have grown to be archetypes of observation and shifting perceptions of our realities.

Like Paul Cezanne’s multiple paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire in southern France or Etel Adnan’s regular examination of Mount Tamalpais in California, George’s domestic objects are a starting point to explore the possibilities of painting. Looking carefully at the same objects each day provokes curiosity; each artwork then represents an opportunity to depict a variety of environments, relationships amongst visual elements, and structure of a picture.

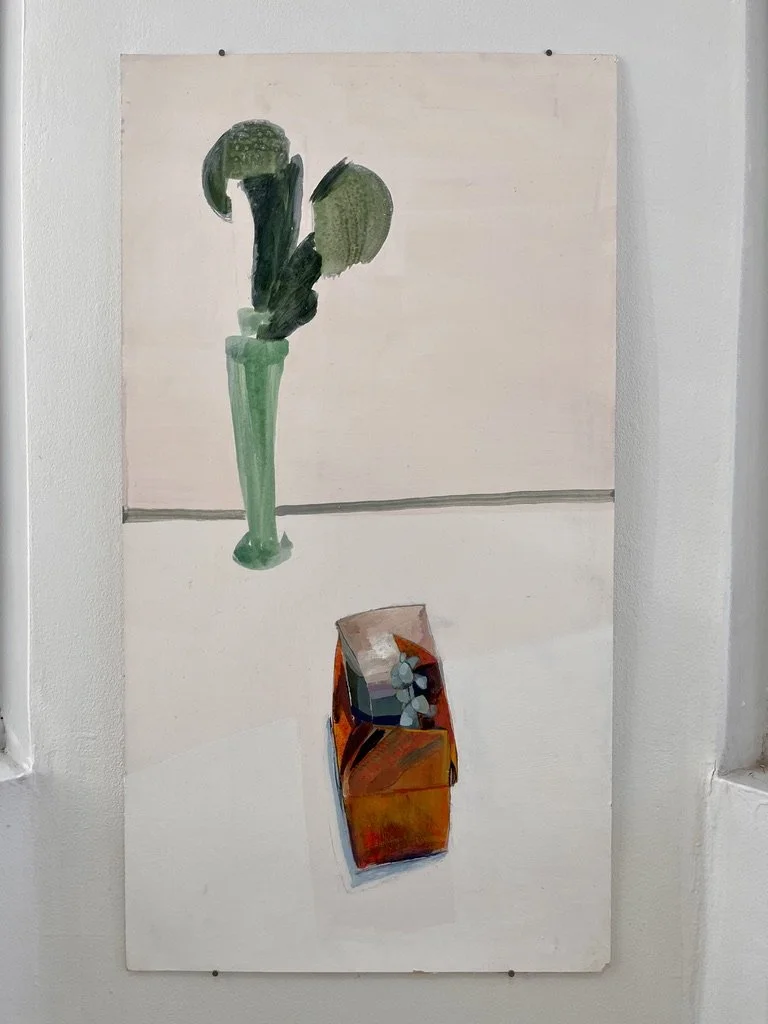

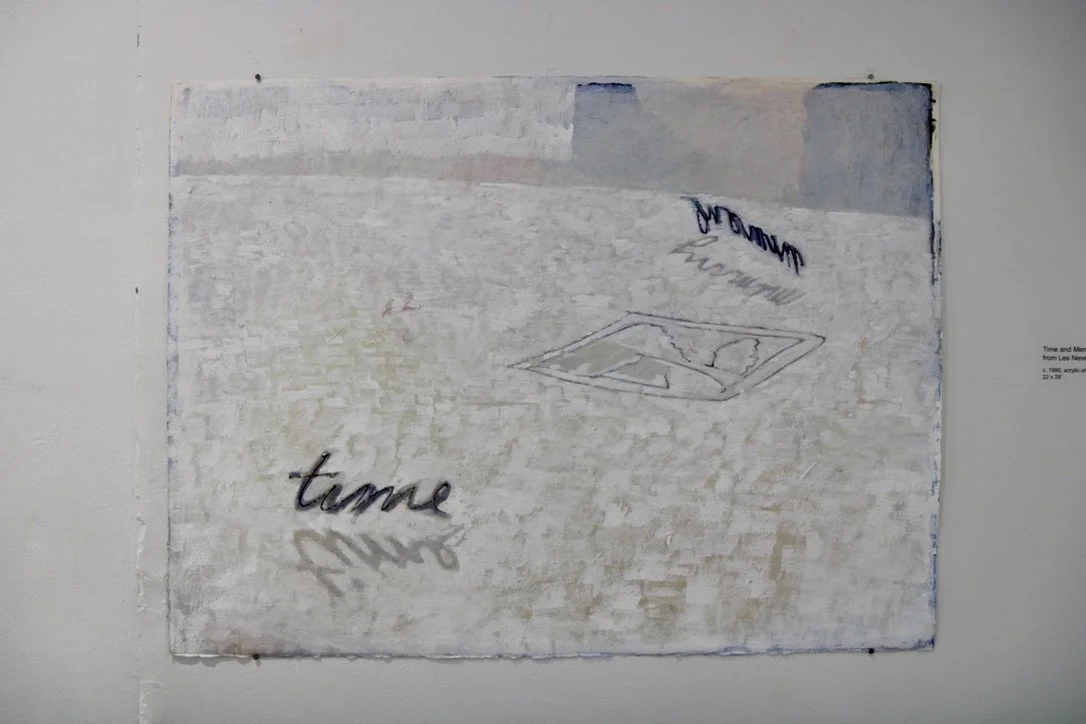

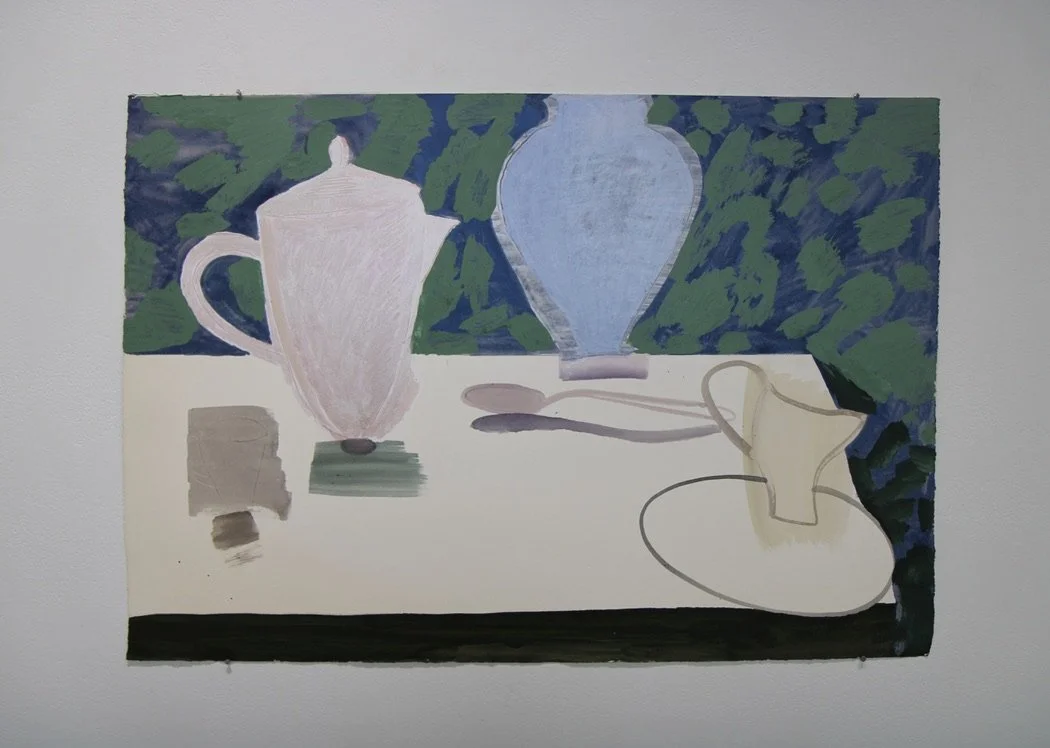

A shift in George’s work occurred in the early 1980s. Akin to Cezanne, he evolved from illusionistic depictions of depth, and moved towards the interplay of formal elements: shape, colour, pattern, and texture. Into the 1990s, many of George’s works emphasized the surfaces of the canvas or paper themselves. The precise characteristics of the objects are subsumed in favour of the tonal and structural demands of the picture. Planes of colour are flattened, but not enough to be completely reduced to the non-representational or to do away with narrative.

For example, The Coming of Spring retains George’s habit of depicting an interior space with a view to the outdoors. But this time our attention is immediately drawn to the large washes of paint thinly applied on the canvas. Combined with the movement of line, the bloom of paint into the canvas, and the curves of the cups and vessels, an overall atmosphere is created that gives the impression of being at the beach. In Conjunction of Space, the legs of a sawhorse lead our eye up to the draped fabric, past the yellow box that obscures a vase - whose plant leaves interrupt the long line from the bottom of the picture upwards - and to the large rectangle that occupies the upper left half of the composition. The overall space is not flattened, but it is brought forward, making us contend with what we are viewing.

In Glass, Vase, and Picture Frame, the sawhorse is not visible, but the toned down, shaded fabric forms a surface that separates us from what lies beyond. The same large rectangle in Conjunction of Space is present in the background of this work, yet here it asserts its presence where the edge of the table ends, in the lower left corner. In both paintings, our tendency to label and define arises: what is the rectangle? Why does it occupy so much space? What is its purpose? Considering the acts of looking, seeing, and exploring in George’s practice, it may itself be an archetype: a blank canvas that represents the many possibilities of creation, borne through wonder and questioning. After all, a purpose of art is not to render precisely what we see in reality, but to shift our perceptions to what the visible world conceals: the unseen forces, the invisible mysteries.

George Glenn, "November Room" (both images), 1994, ink and watercolour on paper, 7 x 11"

George Glenn, "Still Life with Round Bowl and Chinese Box," 1993, acrylic on paper, 15 x 22.5"

George Glenn, "Conjunction of Space," 1993, oil on canvas, 40 x 32"

George Glenn, "Glass, Vase, and Picture Frame," 1993, acrylic on paper, 30 x 32.5"

George Glenn, "The Coming of Spring," 1993, acrylic on canvas, 45 x 59"

George Glenn, "Chocolate Box," 1992, acrylic on paper, 32 x 17"

George Glenn, "Self Portrait: 11th Street Studio," 2003, graphite on paper, 18.5 x 16"

George Glenn, "Single Rose," 1992, acrylic on paper, 30 x 22.5"

Top: George Glenn, "Field with Crocuses," watercolour and collage on paper, 5 x 5" Bottom: George Glenn, "Large Crocuses #2," watercolour and collage on paper, 3.5 x 5.5"

George Glenn, "Large Crocuses #1," watercolour and collage with gold leaf on paper, 3.5 x 5.5"

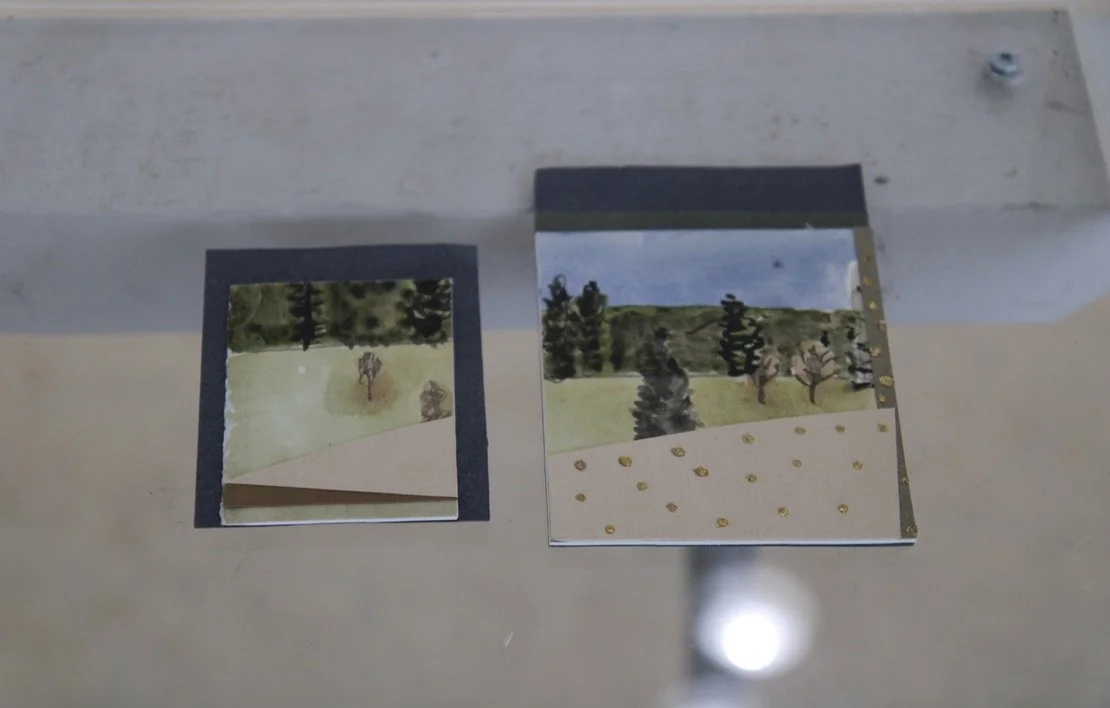

Left: George Glenn, "Miniature Landscape," watercolour and collage on paper, 2.25 x 2" Right: George Glenn, "Small Landscape with Gold Dots," watercolour and collage with gold leaf on paper, 3.25 x 3.25"

George Glenn, "Green Square," 1990, oil on canvas, 42 x 36"

George Glenn, "Time and Memory: Postcard from Les Neven," c. 1990, acrylic on paper, 22 x 29"

George Glenn, "Still Life with Andree's Coffee Pot," 1993, acrylic on paper, 21 x 30"

George Glenn, "Pattern Paintings," 2003, gouache on paper, 7 x 4"

George Glenn, "Self Portrait #28," 2002, oil on canvas, 20 x 10"